OPPORTUNIST VIEW

ПОГЛЯД ОПОРТУНІСТА

Throughout modern history, authoritarian regimes supported by the Soviet Union or russia have faced strikingly similar downfalls. Leaders propped up by moscow often relied heavily on external military and financial support to maintain power, while failing to address the deep-rooted grievances of their populations. This overdependence left them vulnerable when geopolitical realities shifted, resulting in dramatic collapses.

The recent reports of Bashar al-Assad’s flight from Syria amid growing unrest and resource constraints in russia highlight a recurring pattern. From Honecker’s extradition after moscow’s withdrawal of protection, to Viktor Yanukovych’s flight to russia during Ukraine’s Revolution, history shows that when soviet/russian-backed regimes falter, they often crumble swiftly and decisively. The history – whether in Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Ethiopia, or Eastern Europe – underline a consistent theme: you cannot rely on russian patronage.

This piece probes into cases of soviet and russian-backed leaders who fell from grace and examins some broader implications for contemporary geopolitics. Will Assad’s regime become the last cautionary tale of misplaced reliance on putin or are there still going to be others who would try their luck with moscow?

1. Propped Up and Knocked Down: The Pattern of Glorious Collapses of russia’s Clienteles

Afghanistan offers one of the clearest examples of how reliance on Soviet support can doom a regime when external backing fades. In 1979, the Soviet Union orchestrated a coup to remove the Hafizullah Amin, installing Karmal as the leader of Afghanistan. The move was intended to subdue the country under a compliant, moscow-aligned government. However, Karmal’s regime depended almost entirely on soviet military and economic aid to survive, lacking both domestic legitimacy and the ability to address a growing insurgency.

The presence of over 100,000 soviet troops in Afghanistan during the 1980s was pivotal in maintaining Karmal’s tenuous hold on power. His administration failed to win the support of Afghanistan’s fragmented society and declared Marxist policies alienated traditional and religious communities. By 1986, moscow replaced Karmal with Najibullah, hoping his leadership would prove more effective. After the soviet withdrawal in 1989 Najibullah’s forces quickly lost ground. In 1996, he was captured and executed.

The case of Ethiopia provides another striking example of a regime that collapsed as soviet support waned. Mengistu Haile Mariam, the declared Marxist leader of Ethiopia, ruled from 1974 to 1991 with the heavy backing of the soviets. Installed after a military coup that overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie, Mengistu sought to transform Ethiopia into a communist state, relying on soviet aid to suppress internal dissent and fight a devastating civil war. For some time, this assistance enabled his regime to maintain control despite widespread opposition and humanitarian crises, such as the catastrophic famine of the mid-1980s. However, as the soviet union began to collapse in the late 1980s, Mengistu could no longer maintain the power and by 1991 was forced to flee.

Honecker’s fate encapsulates another example how shifting geopolitical reality can turn a once-powerful moscow-dependent ruler into an outcast. Honecker ruled East Germany from 1971 until October 1989, presiding over one of the most rigid communist states in the Eastern Bloc. Backed by the Soviet Union, he was a staunch defender of the Berlin Wall. Under mounting public pressure, his ousting by the members of Politburo was actually orchestrated by moscow. In 1990, as East and West Germany unified, Honecker fled to moscow, seeking protection from the soviets. Initially granted refuge, Honecker’s fortunes changed after the dissolution of the soviet union in 1991. With Russia shifting its stance, Honecker was extradited back to Germany in 1992 to stand trial, including for the deaths of those who attempted to flee the GDR across the Berlin Wall. His extradition reflects uncertainty of moscow’s promises, which can change with its changing foreign policy priorities, leaving the former dependent authoritarian rulers exposed to justice.

The Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan of 2005 forced the resignation of Akayev, the countries first president after independence from the Soviet Union. Akayev faced mounting public anger over corruption, nepotism, and growing inequality and even strong backing from russia could not shield him from being driven into exile to moscow.

In 2010, Kyrgyzstan’s second president, Bakiyev, met a similar fate. He quickly lost public trust due to authoritarianism and nepotism. As a result of widespread protests, which escalated into violent clashes, Bakiyev fled the country. Despite maintaining a military base in Kyrgyzstan, moscow failed again to protect its clientele when faced with overwhelming domestic unrest.

All these cases reveal the inherent failure of reliance on moscow patronage – inability to build a viable society and working economy, capable of sustaining itself without external lifeline. This lesson also resonates in other states, where soviet/russian-backed governments overestimated the power of their patron.

2. Ukraine’s Arms Resistance: A Catalyst Shattering moscow’s Support for Authoritarian Allies

The situation with Yanukovych fleeing Ukraine proves the general pattern as far as the fate of the russian backed rulers are concerned, although it is probably the only example, when the ouster of the pro-russian leader triggered a full-fledged military aggression from moscow. The special place of Ukraine in russian historic grievances prompted a forceful reaction from moscow, which in fact became fatefully consequential for russian geopolitical aspirations and clientele in other regions of the world.

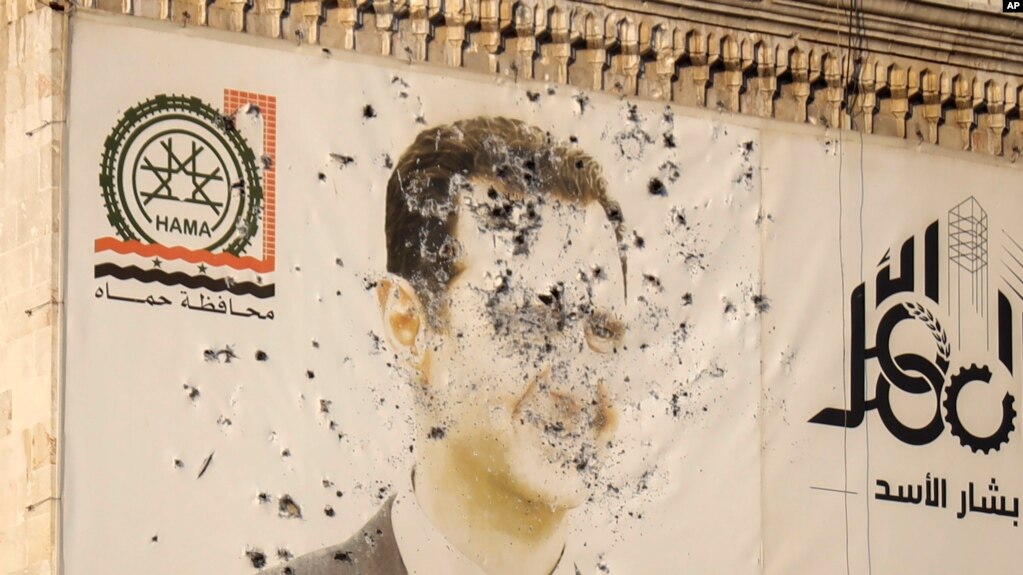

The situation in Syria highlights a recurring theme: reliance on russian support can bolster authoritarian regimes in the short term but leave them highly vulnerable in the long term. Since the start of Syria’s civil war in 2011, Assad’s regime has relied on external allies, particularly russia, to maintain power. In 2015, russian forces intervened directly, launching a devastating air campaign that turned the tide in Assad’s favor and allowed him to regain control over significant portions of Syrian territory. However, after russia started its full-fledged aggression against Ukraine, its ability to sustain the Syrian operation has evaporated and as a result an Assad’s regime collapsed.

As with other cases, the fate of Assad’s regime underscores the limits of moscow’s power in sustaining long-term stability. Assad fled to russia, where he reportedly sought asylum. This development underscores moscow’s overstretched capabilities, as it grapples with the aggression against Ukraine and waning resources. Losing Syria is a major blow for russia – strategically jeopardizing its key military installations in Tartus and Khmeimim and the ability to project force in the Middle East and in Africa, and also undermining claim of being a global power. The breakdown of Assad’s government further reinforces the fragile nature of regimes that rely on moscow’s support, raising questions about russia’s ability to maintain influence across other regions and countries with similar regimes.

Conclusion

The downfall of countless soviet and russian-backed regimes paints a damning portrait of moscow’s consistent failure to sustain its “clients.” From Kabul to Damascus, moscow’s promises of stability and strength often turn out to be Trojan horses—propping up authoritarian rulers just long enough to entangle them in a web of dependency before the winds shift. The collapse of Assad’s regime in Syria serves as a fresh reminder: aligning with russia is a gamble with very bad odds.

For russia, the message of these repeated failures is clear. Its legacy as a geopolitical patron is one of betrayal, incompetence, and strategic shortsightedness. While moscow dreams of projecting great-power status, it seems more adept at accumulating political liabilities and hastening the collapse of the very regimes it supports. It also suggests a growing strain on its ability to project influence abroad. The collapse of its allies—often amid dramatic revolutions or military defeats—raises questions about moscow’s long-term strategy. The loss of allies like Assad not only undermines russia’s image but exposes the inherent weaknesses of its model of influence: heavy-handed intervention, hollow financial promises, and complete disregard for local legitimacy.

For authoritarian rulers still clinging to moscow, the record of diminishing russian returns offers a stark warning: don’t get too comfortable, as moscow’s resources stretch thin the weight of external patronage cannot sustain regimes indefinitely. Whether it’s Belarus’ Lukashenko, Venezuela’s Maduro or clientele in the African continent, they should look at the wreckage of moscow’s former “friends” and ask themselves: How long before we’re next? The path to moscow’s embrace is a slippery slope to irrelevance, exile, or worse. If regimes truly wish to avoid the ignominious ends of Karmal, Yanukovych, or Assad, their best bet is to chart a course far away from the Kremlin’s orbit.

The collapse of regimes supported by the soviet union and russia underscores a recurrent lesson in global geopolitics: no government can endure solely on external backing. These cases highlight three critical vulnerabilities. First, foreign dependency often alienates local populations, who perceive these leaders as proxies for external powers. Second, without addressing corruption, economic mismanagement or repression, these governments fail to build legitimacy, leaving them unable to weather internal dissent. Lastly, shifting geopolitical priorities mean that foreign patrons may eventually withdraw their support when the cost outweighs the benefit, leaving these regimes exposed. The collapse of Assad’s regime further underscores the enduring relevance of this pattern.

These cases illustrate a critical lesson: ultimately, no amount of foreign intervention can replace a foundation of stable governance and legitimacy.

DEXTER KRAM

International Law and Foreign Policy expert

ДЕКСТЕР КРАМ

Експерт з міжнародного права та зовнішньої політики